HISTORY

The seeds of community were sown in the early 1900’s.

A manong stood on Kearny Street and reminisces…

“I remember in 1910, the street cars on Kearny Street were pulled by four horses. The streets were all wood. The milkman delivered the milk in his horse and wagon. He delivered it to the St. Paul Hotel. There were no streets in Chinatown either, it was all wood. Montgomery Street was all water during that time. There was one park in Chinatown . They call it Portsmouth Square. It was so wild…

Benny’s Cigar Store on Clay and Kearny was built in 1915. This was an old Cigar Store. Goes back to the time of the Exposition. This was owned by the Blaser Brothers Co. They used to have a Bail Bond office here. I am 85 years old, and had this cigar store for 25 years. I also remember the Santa Maria Restaurant. It was on Jackson near Kearny Street. It was owned by the Santa Maria Brothers. This was a Visayan restaurant.

There were cable cars on Clay and Washington Streets. This was about 1918. The fare was five cents. Broadway was the dividing line of Italian town. It went all the way to the wharf.

There were three Filipino barbershops on Kearny Street. One next door to the International Hotel. This was Tino’s Shop. And next door to that was the Bataan Drug Store, the Bataan Pool Hall, the Bataan Restaurant.

And across the street where Mike’s Pool Hall is now, I mean Lucky-M that used to be a clothing store in 1930 or 1928 or 1929, he sold this building to a Filipino old timer, then they made this into a pool hall. The first owner’s name was Julian, and the second, a Filipino boxer name Tino. He owned it for a long time.

Another Filipino name Samposa, from Mindanao, wants to buy it for $3,500 but was turned down. And Muyco and his wife took it over. They still manage the pool hall. The pool hall has a history all he way up to now. The Filipino boys all know each other. We are drawn together. We all come from the same place. We feel at home here.”

From 1920-35 there was a filipino male population of 39,328. Legislation forbid Filipinos from owning land or setting up businesses. They were to be kept moving, remain transient. They stayed in labor camps, rooming houses and hotels.

The International Hotel was one of these. “Manilatown,” the Kearny/Jackson Street area of San Francisco, became a permanent settlement, a convenient culture contact. It was the home field-workers returned to, where merchant marines lived while in port, where distant relatives and friends could be contacted, where they could enjoy the security of a common culture.

Immigration laws re-enforced the role the International Hotel played as a family with the social protection it provided. The Filipino community in San Francisco existed in groups dictated by economic necessity and blood brotherhood. The International Hotel became a symbol for an entire minority community.

About 1954, the International Hotel became significant for yet another reason. Enrico Banduccci, opened his original “hungry i” (hungry intelectual) nightclub next door to Club Mandalay in the basement of the International Hotel where performing artists got their start, such as: Nina Simone, the Smothers Brothers, Lenny Bruce, the Kingston Trio, and “Professor” Irwin Corey to name a few.

Urban Renewal

“This land is too valuable to let poor people park on it.” So said Justin Herman, Executive Director of the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, in 1977 to give credibility to the “urban renewal” project in San Francisco that sought to buy up buildings and evict people who were poor, old, black and brown. In the Fillmore, it was known as the “negro removal” plan and in downtown San Francisco, the International Hotel of Manilatown, became the center of the movement against ideologies like those of Justin Herman. The longest eviction battle to date was one result of this movement. The commitment to affordable housing and the fight for social justice in the Filipino and Asian communities was another. The story of the I-Hotel is one of great significance as we enter a more modern era of gentrification in the city.

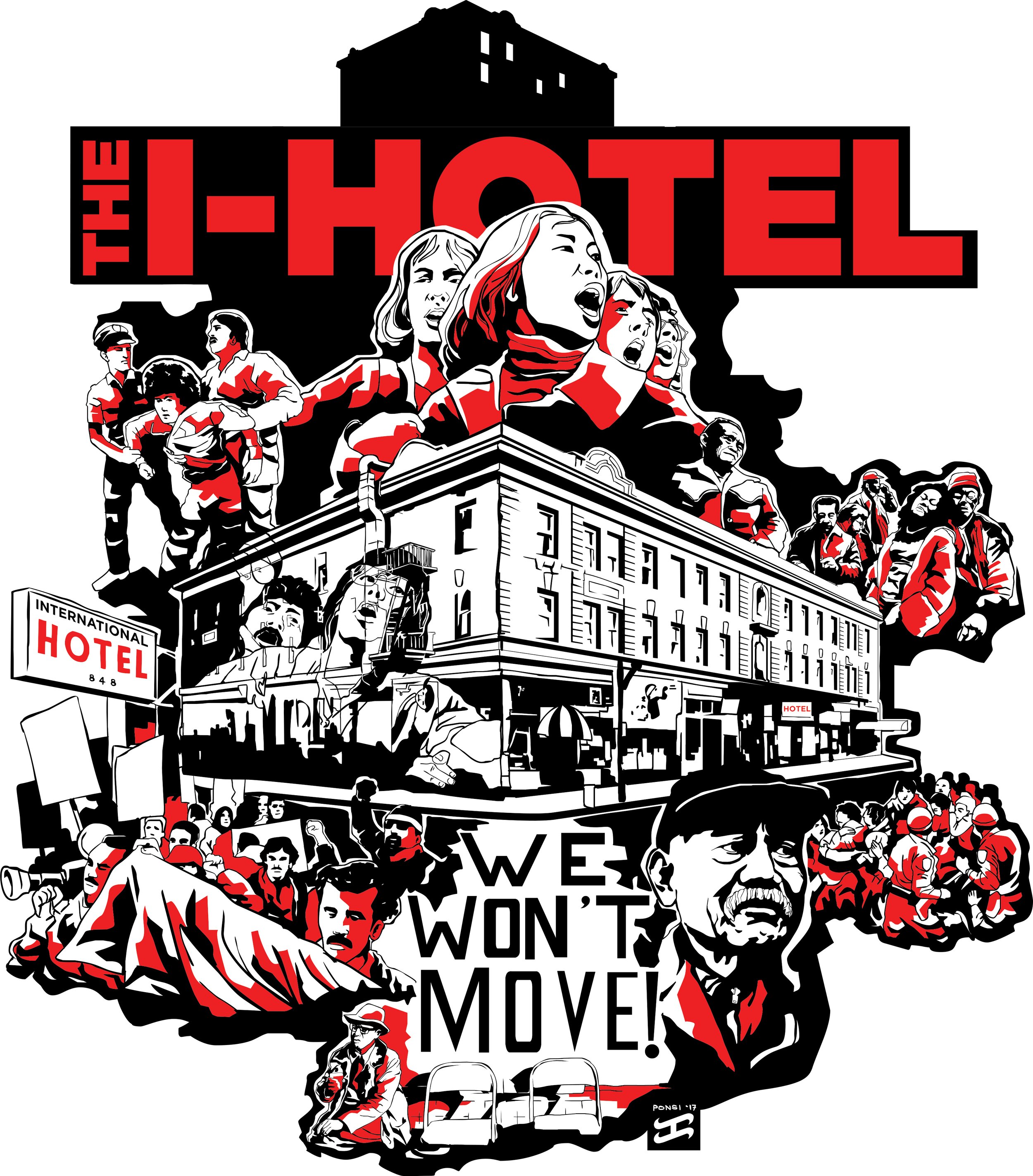

The I-Hotel

"The International Hotel was a low-income residential hotel that became the most dramatic housing-rights battleground in San Francisco history. As a center for Filipino and Asian American activism in the 1970s, the building housed nearly 150 Filipino and Chinese seniors, three community groups, an art workshop, a radical bookstore and three Asian newspapers. The I-Hotel stood on the last remaining block of Manilatown, a once-thriving Filipino neighborhood that was gradually displaced by San Francisco’s expanding financial district.

The Fall and Rise

From 1968 to 1977, landlords of the hotel tried to evict the residents and build a parking lot. Resisting eviction for almost a decade, the tenants organized a mass-based, multiracial alliance which included students, unions and churches. During the final 3am eviction on August 4, 1977, over 3,000 people unsuccessfully defended the I-Hotel from hundreds of club-wielding riot police. The building was demolished in 1979, and it remained a vacant hole for over two decades. Thanks to a concerted effort by local neighborhood groups, the I-Hotel was rebuilt in 2005, providing 104 units of low-income senior housing and the International Hotel Manilatown Center to continue the legacy of Manilatown."

Courtesy of Claude Moller